Photo by naomi tamar on Unsplash

Scope of the issue

Commonly, in non-fiction there is an index at the end to allow readers to look at a collated list of topics that are contained within with page numbers where they are discussed, so the reader can go directly there without having to scan through the whole book each time.

Books written in LaTeX can make use of the imakeidx package to generate the index.

The package is well documented, and I won’t discuss it in any real detail here, as there are tutorials online for how to use it.1

What’s important is that each term that you want to index is followed by the command \index{TERM}.

So, say that you want to index second in the text below, you’d add in \index{second} like so:

A second\index{second} is one of the fundmental units of time.

In an ideal world, you would create the index as you write, so that each time you put in a term, you already put the index marker in the source text. However, writing a book doesn’t really work that way and, take it from me, what you end up writing will rarely match exactly what you set out to write. It’s better then to do the index at the end of the project, when you can see the book in context and know the contents.

The problem is, then you have to go through your source files and put the \index{TERM} command after everything you wish to index.

That’s a daunting prospect for a long book.

So, what is the best way to do this?

The obvious

Suppose you have gone through your work, noted which are the important terms you want in the index, conceptualised how they all group together (i.e. what stands alone, what categories can be nested under others etc.) and you’re ready to do it. The obvious thing to do is to go to the beginning of the pdf, start reading, and wherever you see something you want to index, run synctex, find the item in the source, and input the relevant index marker. Easy, right? This is certainly one way to do it, and not an inherently bad one, but there are some downsides. It is repetitive, in many many cases redundant, as you will enter the same text for the same item in various different places, and most likely, you are going to miss some. Why? Well, if you have 50 items you want to index, you need to keep the entire group of 50 in your mind whilst you read through. You may not miss some, but chances are you will. So, whilst this is an option, it seems there is a better way. Let’s call this Plan B for now.

Replace All with a GUI?

As I noted before, indexing in LaTeX is pretty easy.

Suppose that you want to index second, then all you need to do is add \index{second} after every instance of second. Simple.

It effectively boils down to second -> second\index{second}.

There’s two ways of looking at this.

Firstly, one can append \index{second} to every instance of second.

Or you can replace the string second with second\index{second}.

The effect is the same, in the sense that the result is one of appending the index command.

However, the subtle difference is that you replace the original string, but the replacement string contains the original string.

The next obvious solution is that most text editors have a function that allows you to find and replace text.

Usually by hitting something like control/command+f you can get the editor to scan through the document and find the next instance of the string you’re searching for.

Then, depending on your editor, there is often an option to replace that with a different one.

We can then make a simpler version of the procedure above, and for a specific term, programmatically go through the document hitting find and then replace.

Again however, there is a problem.

This is easier than earlier, but still redundant in that you are repeating the same step over and over.

So, how about the replace all option, that will at a click replace every instance of the chosen string with the alternative?

That’s what we’re striving for, right?

The procedure now is simple, hit control+f, enter second in the then click replace all.

Easy.

Repeat that 50 times for your terms, and you have yourself an index.

Right?

Well, yes, but probably not the one you want.

Two problems.

Firstly, language is, frankly, annoying for this task.2

Homophony, where the same string means different things, means that not every instance of the word second is going to be right.

If you want to index the unit of time, then with replace all you may also end up indexing second in the sense of “second place”, which is not ideal.

You may even use the verb seconded, which is going to get conflated with the unit of time.

Again, not ideal.

The second (get it?) issue is that books are long, and best practice with LaTeX is to split long documents up into smaller parts and call them from a main document with the \include{} or \input{} command.

You don’t have to write this way, but if you compile a 300 page document each time, it’s going to take a while and this can be annoying when debugging.

Replace all often only works on a single document, and not for all documents in an entire directory.

So, if you have 6 chapters of a book, all split into different files, then you have to run the same command six times.

We’re starting to zero in on the solution, but we need a better way still, that allows us to replace all in one go, but important (i) quickly check what we’re replacing; and (ii) do all of our source files at once.

Enter bash: find and replace with sed

Doing the same task on a batch of files in one go is ideally suited to using the shell of your computer. There are a number of different shells available, with bash and zsh being the most common on unix based systems (Linux, Mac and BSD, for instance) and powershell on Windows. I’ll use bash in what follows. Find-and-replace can be done on the command line using sed, or ‘stream editor’. It is a very powerful tool, that can also be used to append, as we’ll see later. Changes can be written either to the standard output, in which case you’ll see them on your terminal screen, or written into the source document, or written to a new document. We’ll use the former two.

Let’s see a simple example.

In our directory with the source files, suppse there is a file chapter_1.tex that contains the following text.

A \textbf{second} is one of the fundamental units of time.

There are 60 seconds for each \textbf{minute}.

Beneath the level of the second is the \textbf{millisecond}, the \textbf{nanosecond} and the \textbf{microsecond}.

Second, the term, was borrowed into English from Old French \cite{wiktionary}.

Second to none, the second is the easiest unit to count with.

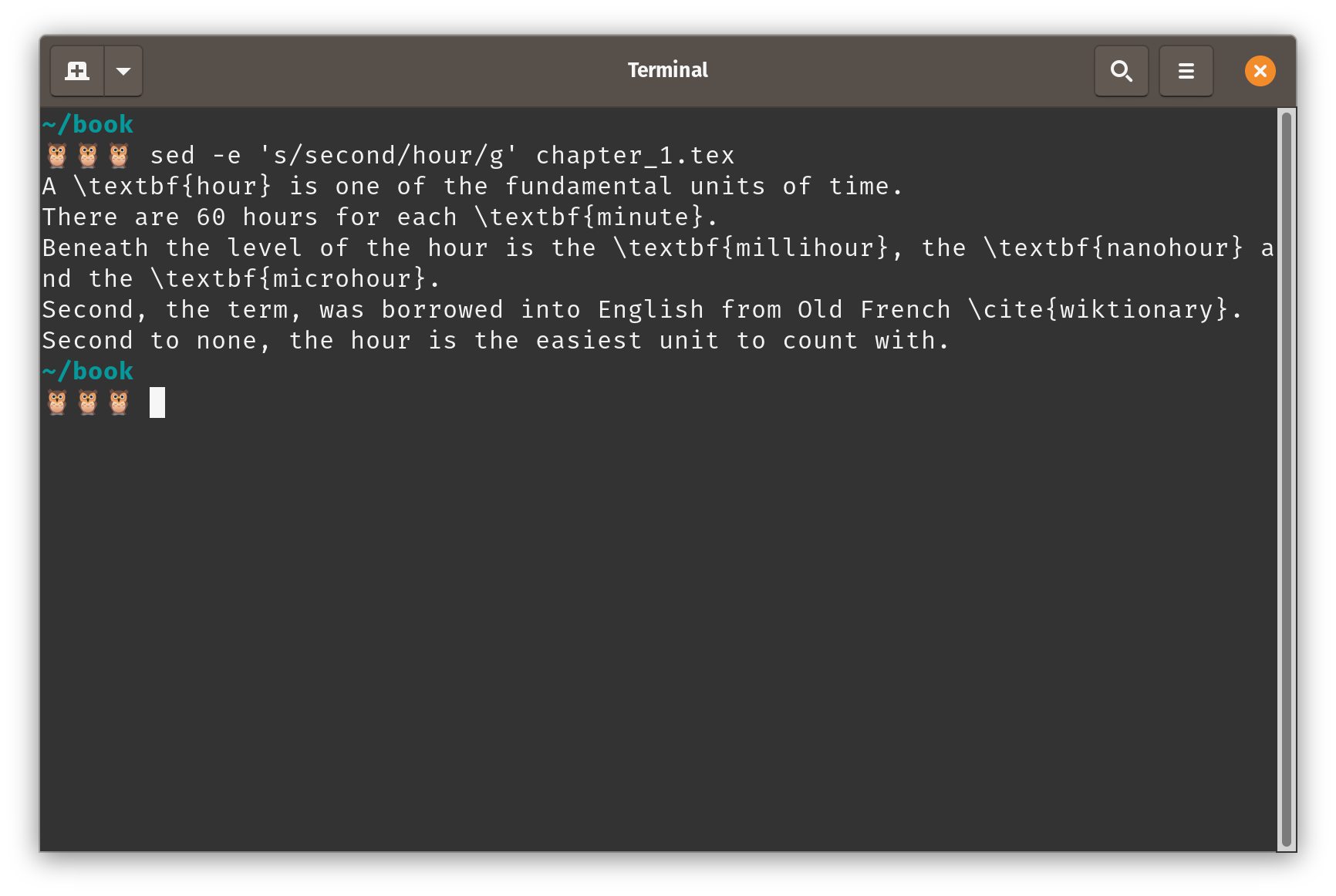

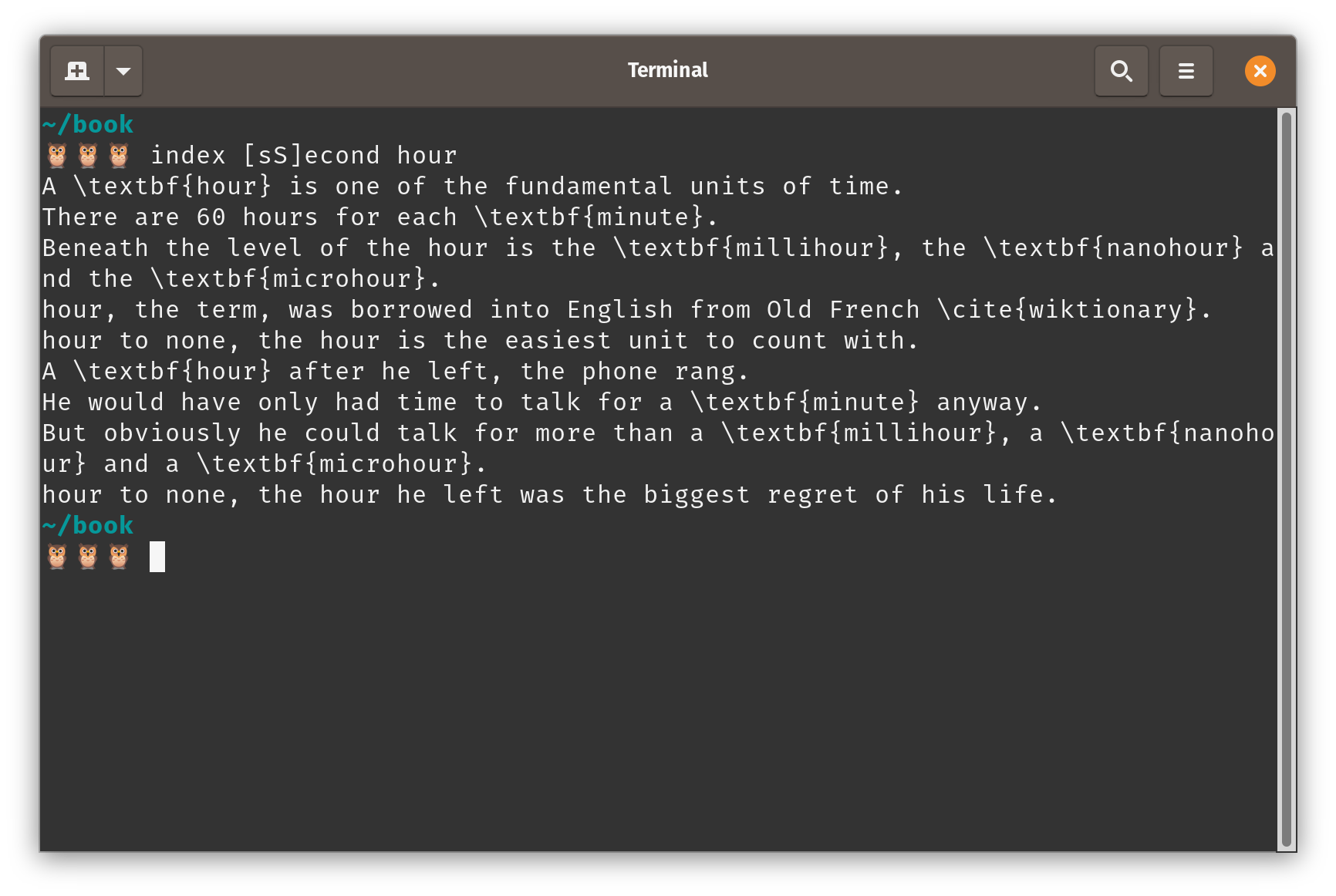

If we want to use sed to replace all instances of second, with, say, hour, then we run the following:

The s prefix indicates the substitution operation, and g suffix indicates that the change should happen globally throughout the file, rather than just the first instance.

Between the slashes, the first string is the original, and the second is the replacement.

sed -e 's/second/hour/g' chapter_1.tex

And this prints the following to the terminal screen:

Find and replace with

Find and replace with sed

Let’s say we run that to check and we’re happy.

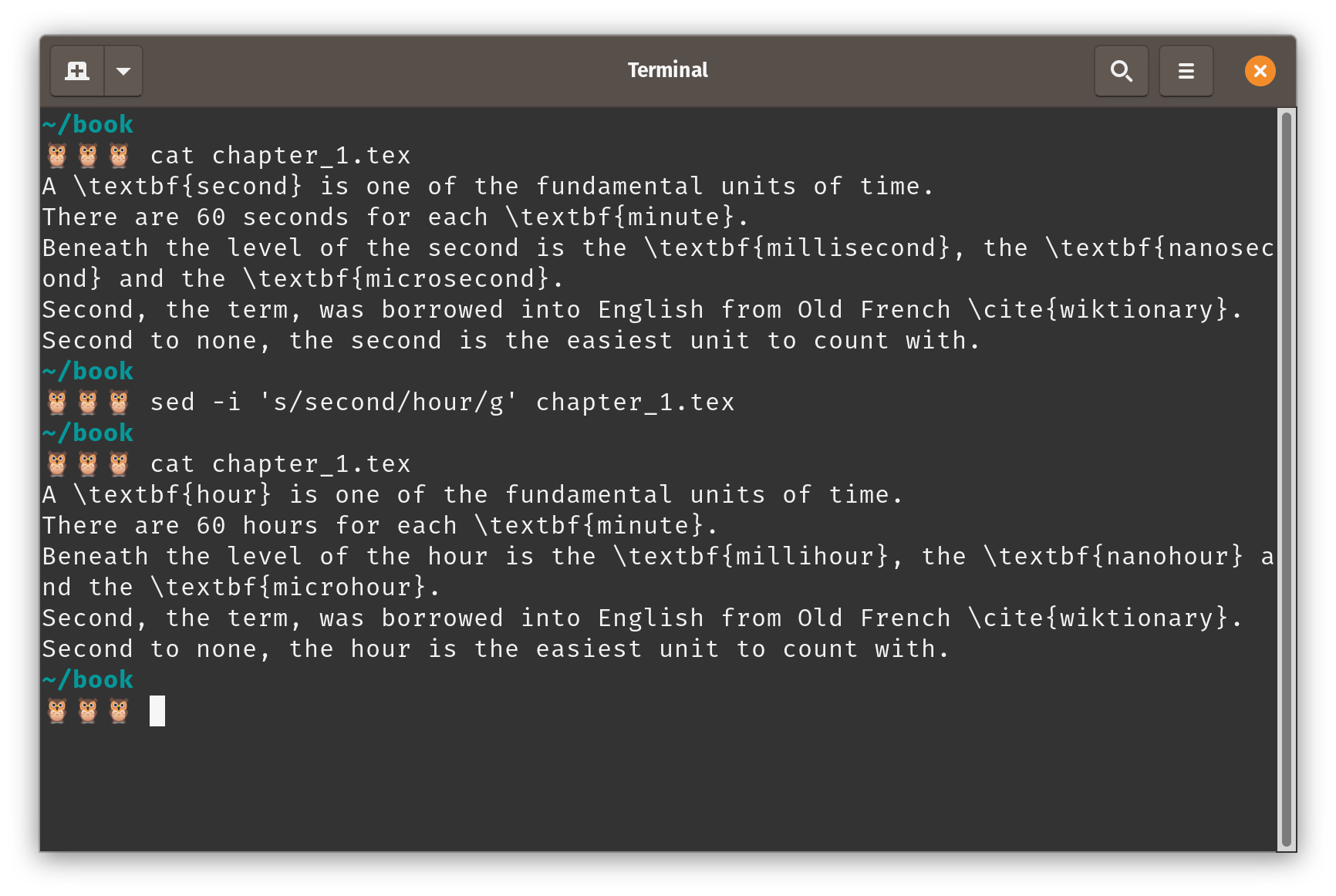

Now we want to make the change in the file, then we replace with -e flag with -i (in place).

sed -i 's/second/hour/g' chapter_1.tex

Compare the result of running cat on the chapter_1.tex before and after the command is run.

Note the differing outputs of running

Note the differing outputs of running cat chapter_1.tex before and after sed

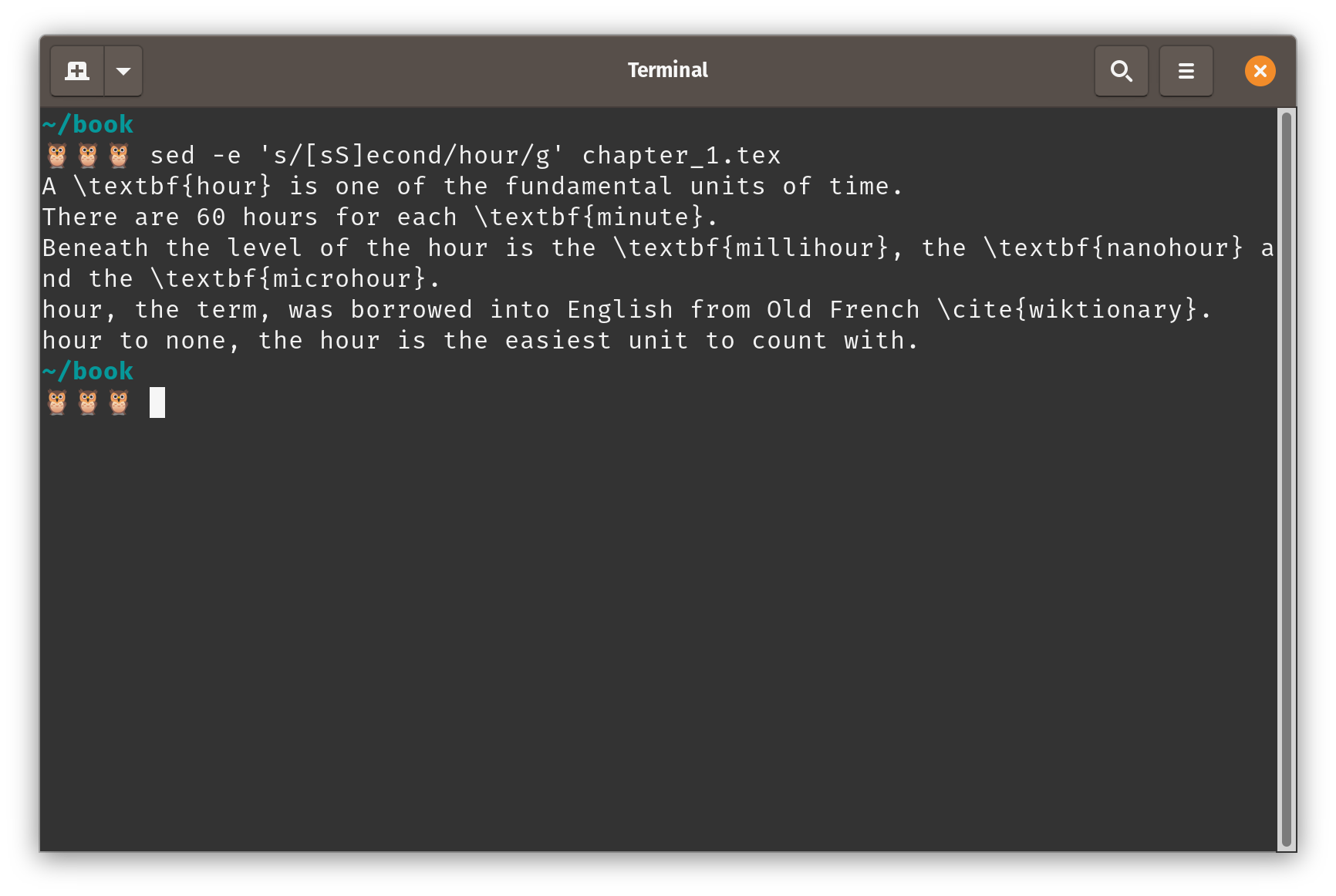

But suppose you also want to change the last instance also, on the last line.

This begins with a capital, so it wasn’t picked up by sed the first time.

Fortunately, sed can be combined with regular expressions, so you can make the query [sS]econd, and the search will pick up both second and Second.

Using a basic regular expression with

Using a basic regular expression with sed

Making a bash function for indexing

Now we have the basics in place of what we need to define a function that we will use for indexing.

Firstly, make a file to store the function.

The name doesn’t matter, so we’ll just call it index.sh.

## to be revised...

function index() {

sed -e 's/'"$1"'/'"$2"'/g' $3

}

Then type source index.sh and the function will be added to your environment.

We’ll revise this function throughout.

Any time you make a change to the index.sh file, you need to run source index.sh on the command line to reimport the function into your environment.

This is used as follows.

Typing index at your terminal calls the function, then the string you wish to replace (the query), the string you wish to be the replacement, and then the file you want to do it for.

Bash will match the first word after index to $1, the second to $2 and the third to $3.

Going back to what we’ve been doing so far, suppose again that we wish to replace second with hour in chapter_1.tex, at the command line run the following:

Nice!

But, we need some refinements. All we’ve done so far is replicate the GUI replace all function. But, we wanted to make it do two more things. We wanted it to allow us to check, to make sure it’s all good, so we don’t blindly replace everything. We’ll soon add this functionality to allow us to note wrong instances, and go back and correct them later. We also wanted to be able to do it for all files in the directory.

Looping over files

Let’s deal with the latter first.

This, we achieve with a simple bash for-loop.

After making this change in index.sh, don’t forget to run source index.sh in your terminal!

## to be revised..

function index() {

for FILE in *.tex

do

sed -e 's/'"$1"'/'"$2"'/g' $FILE

done

}

We now no longer need to specify a file to run sed on, as the bash loop will run it on all files that have the .tex suffix.

Let’s suppose that in addition to chapter_1.tex we have a second chapter, chapter_2.tex, with the following contents:

A \textbf{second} after he left, the phone rang.

He would have only had time to talk for a \textbf{minute} anyway.

But obviously he could talk for more than a \textbf{millisecond}, a \textbf{nanosecond} and a \textbf{microsecond}.

Second to none, the second he left was the biggest regret of his life.

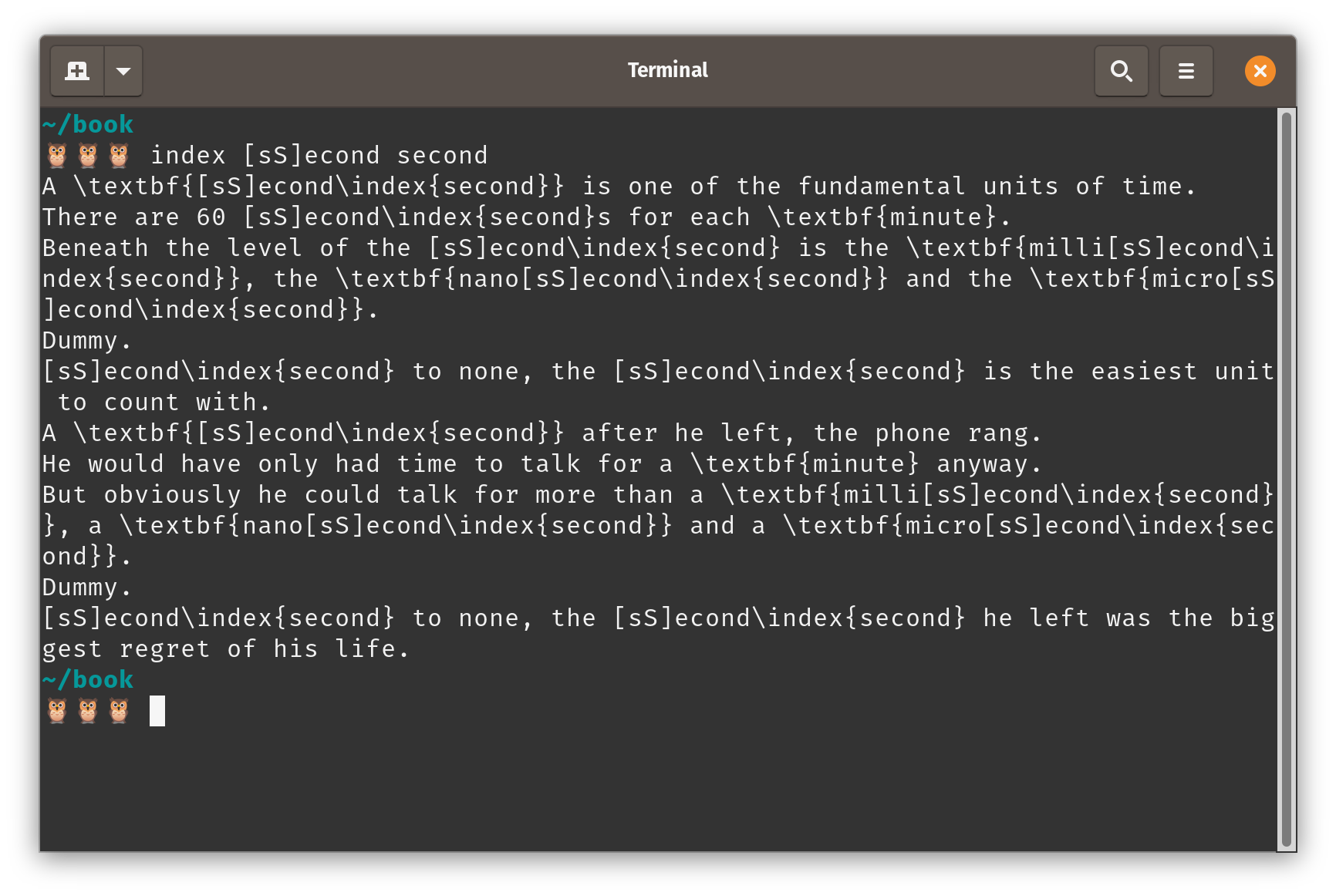

Now, if we run our modified function, we get the following to standard output:

Now we’re looping

Now we’re looping

Making an actual index function

Before moving on though, let’s revise the function to make a proper index.

I’ve been using replacement to demonstrate the use of sed, but recall that we don’t want to replace, but rather append \index{TERM}.

It’s tempting to simply add in $1 in the replacement slot:

## to be revised..

function index() {

for FILE in *.tex

do

sed -e 's/'"$1"'/'"$1"'\\index\{'"$2"'\}/g' $FILE

done

}

But, the query will not always match the replacement, especially if the query involves a regular expression:

This is clearly not what we want.

This is clearly not what we want.

The solution is to use a group in the replacement string.

The escaped parentheses in the query creates a group, which is then referred to with \1 in the replacement string.

## to be revised..

function index() {

for FILE in *.tex

do

sed -e 's/\('"$1"'\)/\1\\index\{'"$2"'\}/g' $FILE

done

}

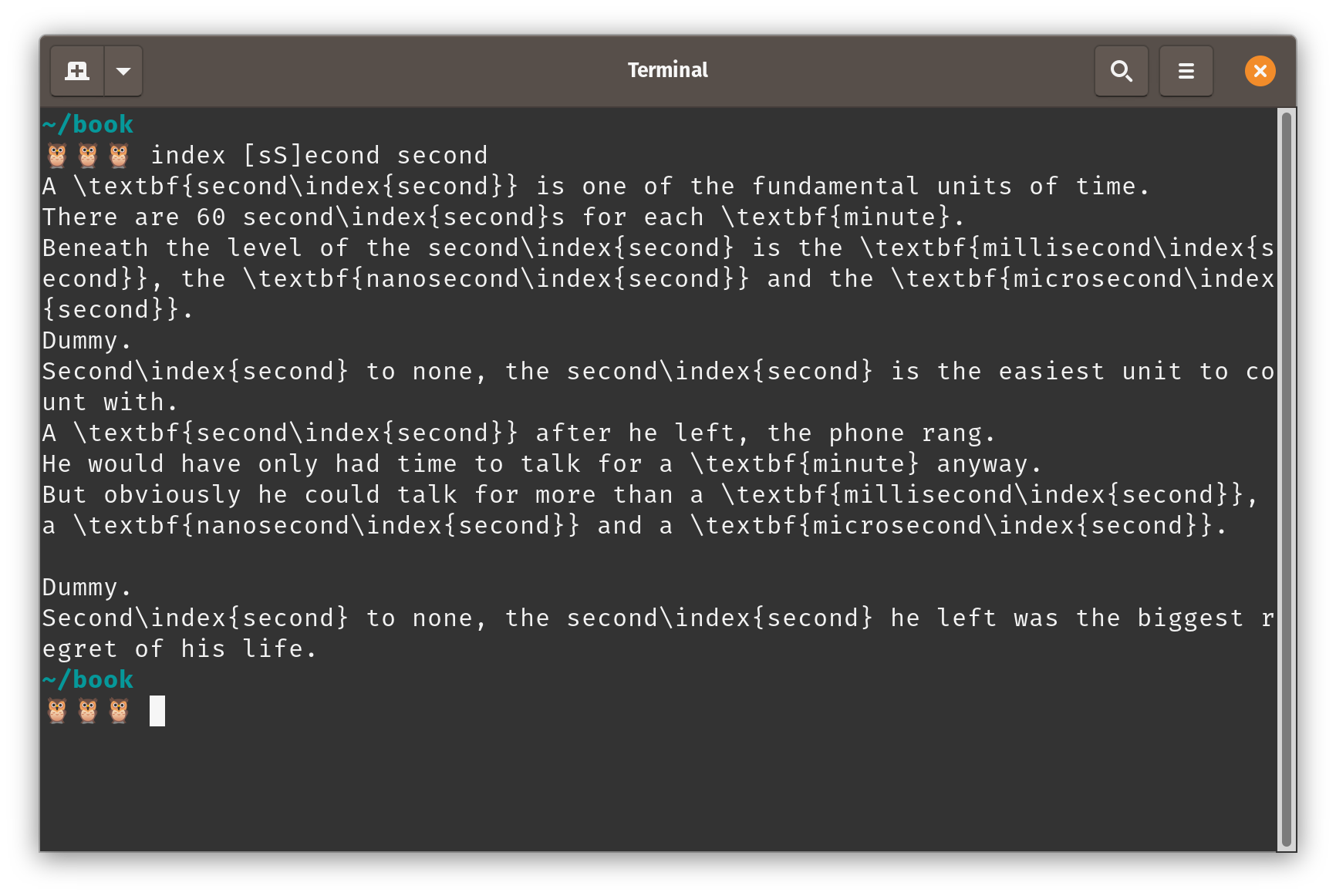

This is better.

However, it’s still not quite right as we’re now indexing a couple of things we shouldn’t.

Firstly, nanosecond, millisecond and microsecond shouldn’t get indexed.

Though they contain the string second, they refer to different things.

Secondly, Second to none has an indexed item in it, but it doesn’t refer to a unit of time here, but second as in ‘second place’.

We can fix the former by refining our query to add in a word boundary at the beginning of the string with \b.

Because there is no word boundary before second in, eg., microsecond, then it doesn’t match the query:

We’re no longer indexing, eg., ‘microsecond’ with ‘second’

We’re no longer indexing, eg., ‘microsecond’ with ‘second’

For the latter case, there is not much we can do. The query matches, as it should do. The problem is, as noted earlier, there are two homophonous uses of ‘second’. These tend to be fairly rare, so it’s best to make a note of where they happen, and fix them by hand later.

Adding in checking

Now we can loop over files, let’s move to the other functionality we want to add, the ability to check before replacing.

Up to now we’ve been printing the output of sed to standard output with the -e flag.

This provides a convenient way to check.

But, we’ve also just been looking at the entire output.

In our toy example, with two files of around five lines each, it’s not a problem to look through and manually check all instanes of the query but this gets unwieldy really fast.

So, we’ll first run the query through grep, add in colour highlighting of the query with --color=always, and also use the -H and -n flags to show file name and line numbers respectively.

This will allow us to quickly scan all and only the instances of the query, and make a note if there are any we will need to fix manually later (such as with the two instances of Second, which don’t fit the ‘unit of time’ meaning).

## to be revised..

function index() {

for FILE in *.tex

do

grep -nH --color=always $1 $FILE | sed -e 's/\('"$1"'\)/\1\\index\{'"$2"'\}/g'

done

}

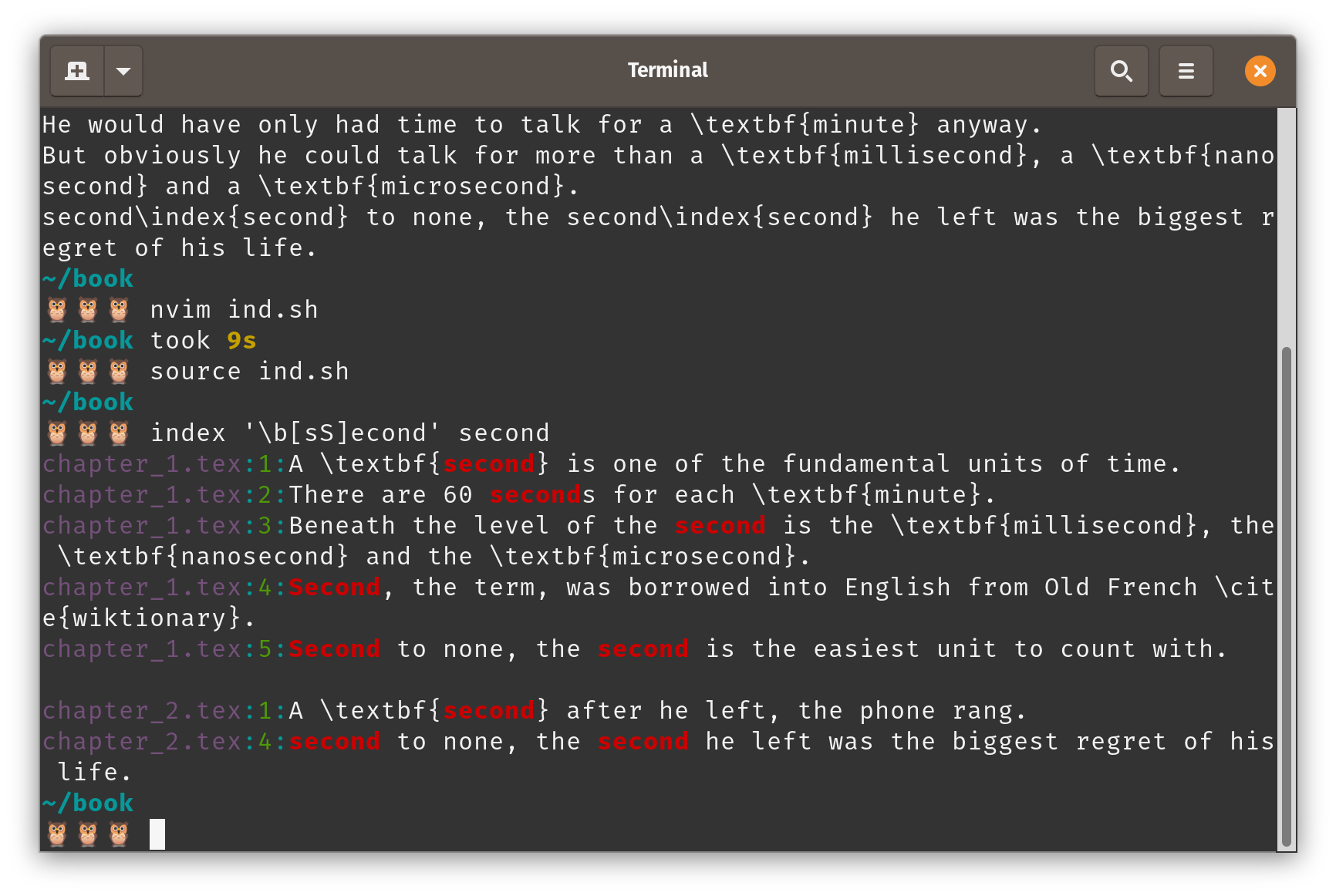

Note the use of the single quotes in the query when we run the command. That’s important for

Note the use of the single quotes in the query when we run the command. That’s important for grep to correctly identify \b

Up until now, we’ve been running sed with the -e flag and previewing the results in standard output on the terminal, which serves as a useful check, but we also want to make the results in the file.

So, as a final step, we’ll add in a second run of sed, this time with the -i flag if the preview looks good.

What we need for this is to add a if-loop into our bash function after the run of sed.

If we’re happy with the result then we continue to run sed -i, if not, the function should abort to give us a chance to refine our query.

We’ll also map the command line input to variables to allow them to be used throughout the function, including within the if-loop:

## Final version!

function index() {

ARG1=$1

ARG2=$2

for FILE in *.tex

do

grep -nH --color=always $ARG1 $FILE | sed -e 's/\('"$ARG1"'\)/\1\\index\{'"$ARG2"'\}/g'

done

read -p 'Is this correct (y/n): ' VALIDATION

if [ ${VALIDATION::1} == Y ] || [ ${VALIDATION::1} == y ]

then

echo "Applying changes to file."

for SOURCE in *.tex

do

sed -i 's/\('"$ARG1"'\)/\1\\index\{'"$ARG2"'\}/g' $SOURCE

done

else

echo "Function aborted, go and refine the query."

fi

}

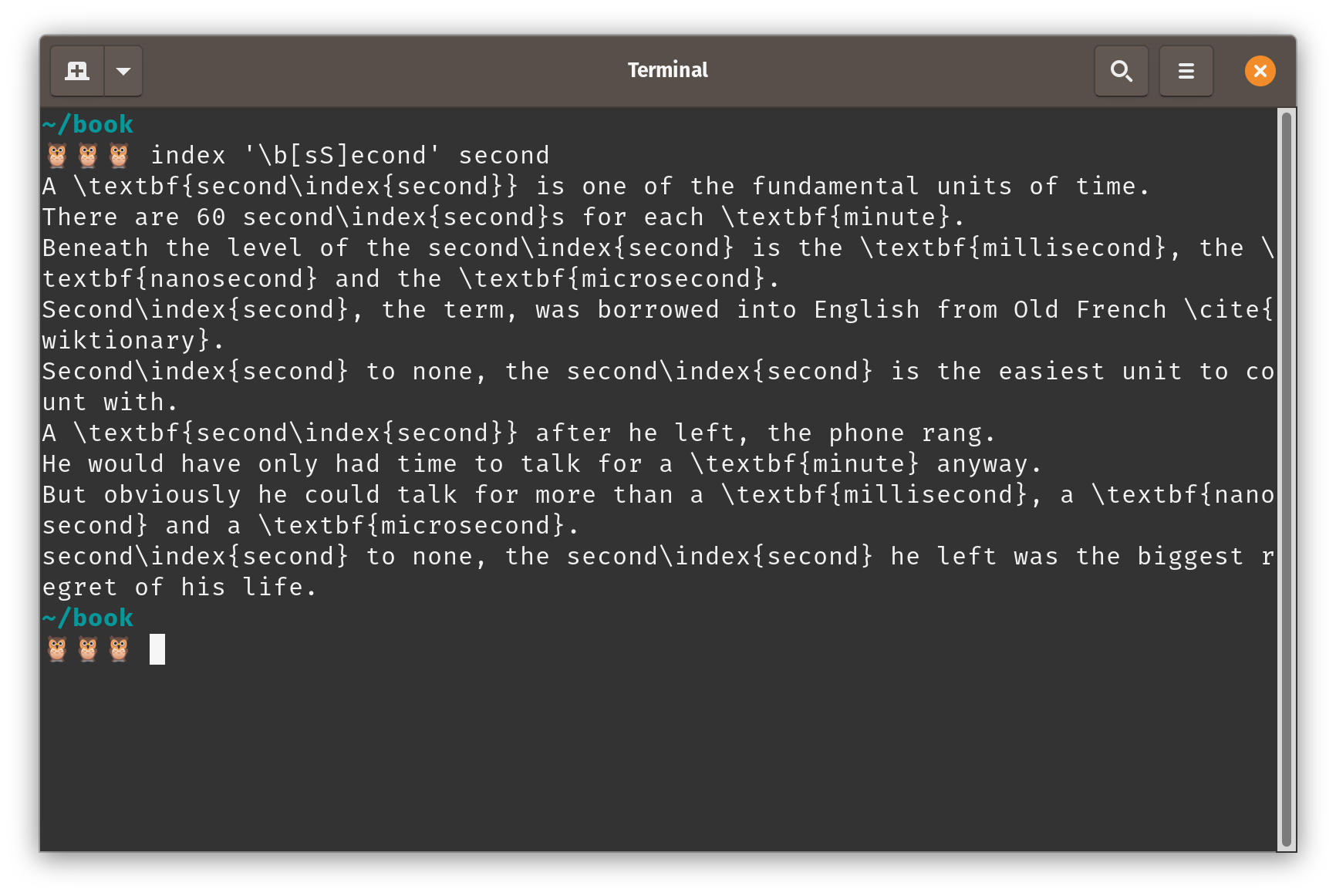

And that’s it!

Now when we want to index a term, like second.

All we need to do is run the following:

index '\b[sS]econd' second

First grep will find the relevant instances, feed that into sed, which will then print to the terminal the suggested changes.

A prompt will appear asking if that is correct, and if you then press y or Y (or type yes or Yes), then the command will run again and sed will this time make the changes in the file.

If not, it will abort and prompt you to refine your query.

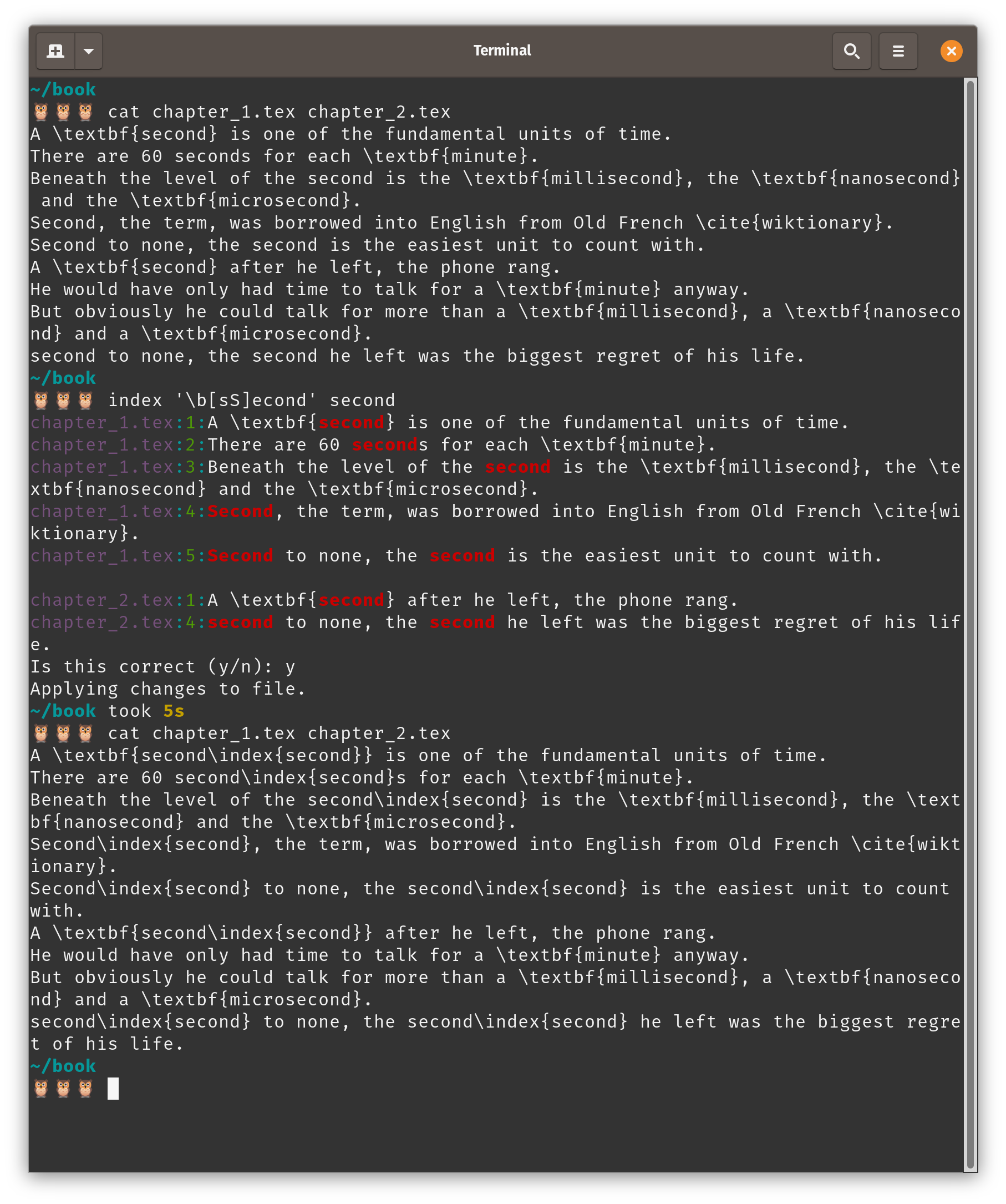

The result:

Running the full function. Note again the second

Running the full function. Note again the second cat output, where the changes have been made in-file.

It’s important to note that this will not do everything for us.

As I said before, language doesn’t allow for a perfect 1:1 mapping between terms and meanings.

In our example files, some instances of Second have been picked up which should not be indexed, as in Second to none.

However, if you refine the query enough, and carefully check before you implement the changes, you can write down the files and locations of the ‘wrongly indexed’ instances and go and manually change them.

This should be easy, given that the grep query, with the -nH flag will tell you which file, and line number the example came from.

Because of the first step of the function, grep tells us that we need to go and manually change line 5 in chapter_1.tex and line 4 in chapter_2.tex.

And that’s that!

Our bash function saves us going through the entire file by hand making the same changes time and time again.

We still need to do some manual editing, but if you take the time to craft the right regexes and combine them with this function, you’ll save yourself a lot of time and energy!