So, so, many things. But, I mean things I wish I knew from a technical standpoint, not just things about academia and/or life in general. The way I handled paper writing and research in the early days of was vastly different from how I do it now. If I had started off this way, it would have saved a lot of time in the long run. It’s true and to be expected that everyone’s work flow evolves over time, but the basic set up one uses has a big influence on how you write, and the amount of time spent doing tasks related to that. I think I’ve got a nice set-up now — certainly not perfect (it’s not something one can measure extensively), but it works for me — and below I share some tips that I’d give to anyone starting their PhD, especially as a linguist, but I think a lot of this holds for most disciplines.

When I started graduate school in Connecticut in 2010, I used the same computer setup that I did when I did my BA studies. That meant, everything was done in Microsoft Office (realistically, 99% Microsoft Word). Quite early on at Conencticut I bought a Macbook Pro, which meant switiching to Apple’s software (I didn’t want to buy Office for Mac, when Pages — at the time – was sufficient for what I was doing). Around 2014, I’d reached the limits of what I could do with this: I’d wrestled with these programs enough for writing, but two journal submissions finally highlighted the need to not waste time anymore on example numbering and bibliography management, so I decided to switch the way I wrote papers to using LaTeX. That, but mostly my wife Beata was using LaTeX and I got intrigued. I wish I’d done it earlier, and learned it at a time I wasn’t writing job and project applications, and my thesis (all at the same time, fun times). This applies not only to using LaTeX, but also to having a streamlined set-up in the way I do now.

Use LaTeX…

The debate of LaTeX vs. what-you-see-is-what-you-get (WYSIWYG) programs like Word and Pages, is well discussed, and can incite strong opinions. Those in favour of LaTeX point to the severance of the writing itself from formatting. LaTeX is written in plain text, and then LaTeX itself handles the formatting very intelligently. In an ideal case, this means one can focus more attention on the content rather than the formatting, which whilst potentially true, is a very idealised version of using LaTeX. It ignores time spent identifying and fixing errors as well as fixing your preamble so that the appearance is how you want it (not everyone, I know) as well as a number of other things that distract from the writing process. Those in favour of WYSIWYG writing point out that the learning curve for LaTeX is outlandishly steep, that collaborations often require using WYSIWYG programs as collaborators don’t use LaTeX, and that some journals — inexplicably — require final versions of paper in .docx format.

I’m a big fan of LaTeX. In my experience it’s mind-numbingly frustrating to learn at times, but once you know it well enough, it’s no less easy than using Word. Whilst many people have a complexity fear of LaTeX — looking at its code out of the blue is duanting if you don’t know what you are looking at — I find that LaTeX is not difficult to use, it’s the diagnosing of errors that is tough and time consuming. Once you know your way around these, then it’s a fantastic tool. For those not versed, here is why you should use LaTeX, particularly as a linguist:

- Bibliography management is simple.

- Numbering of examples is done automatically.

- It will handle formatting mostly well

- It’s probably the best suited software for generating articles with the typesetting requirements that linguistics needs.

- It makes life very easy to use non-latin characters, and to combine accents with them.

There are easier options of writing in plain text (for instance markdown), but these often lack the required support to format linguistics papers. For instance, automatic numbering, glossing alignment, tree drawing, are all not easily done using markdown (there are workarounds).

As I said, I’m not here to give an overview of why LaTeX is good for academic publications. Many of these exist already see here for a general discussion, and for a lingusitics specific set up, see Latex for Linguists (Essex-style), from Doug Arnold and Latex for Linguists (Leipzig-style), from Anke Himmelreich.

…but recognise its limits

Firstly, as noted, LaTeX has a steep learning curve. If you’re only interested in using it to write a single project (paper, thesis) and your entire background is with Word, it’s likely that it’ll be quicker and easier for you to just use Word. If you want to use LaTeX for more projects in the future, then put the time in early and it will save you a lot of time in the future. That’s why I wish I knew it at the beginning. The beginning of a PhD is a great time when you have two things you’ll lack later on: time and motivation, so it’s good to pick up skills then. It does take time and effort to trawl through error messages trying to figure out what the problem was (yes, LaTeX gives you pointers in the console, but they’re often cryptic to most).

Secondly, as this article points out, whilst LaTeX is a great piece of software, it’s still an old piece of software that has developed over many, many years by now. That means that some of the packages that you need to use may conflict, and there’s little chance of an update fixing it. Whilst this is a minor concern in the time I’ve been using it, it does happen. Anyone who has tried to compile in XeLaTeX (e.g. if you’re requireed to use fontspec) and tried to use TIPA for phonetic symbols has likely run into this.

…and use it properly

That said, LaTeX for me is still the best choice for writing articles in. But, there are things that you can do to enhance the experience of it.

Use a good text editor

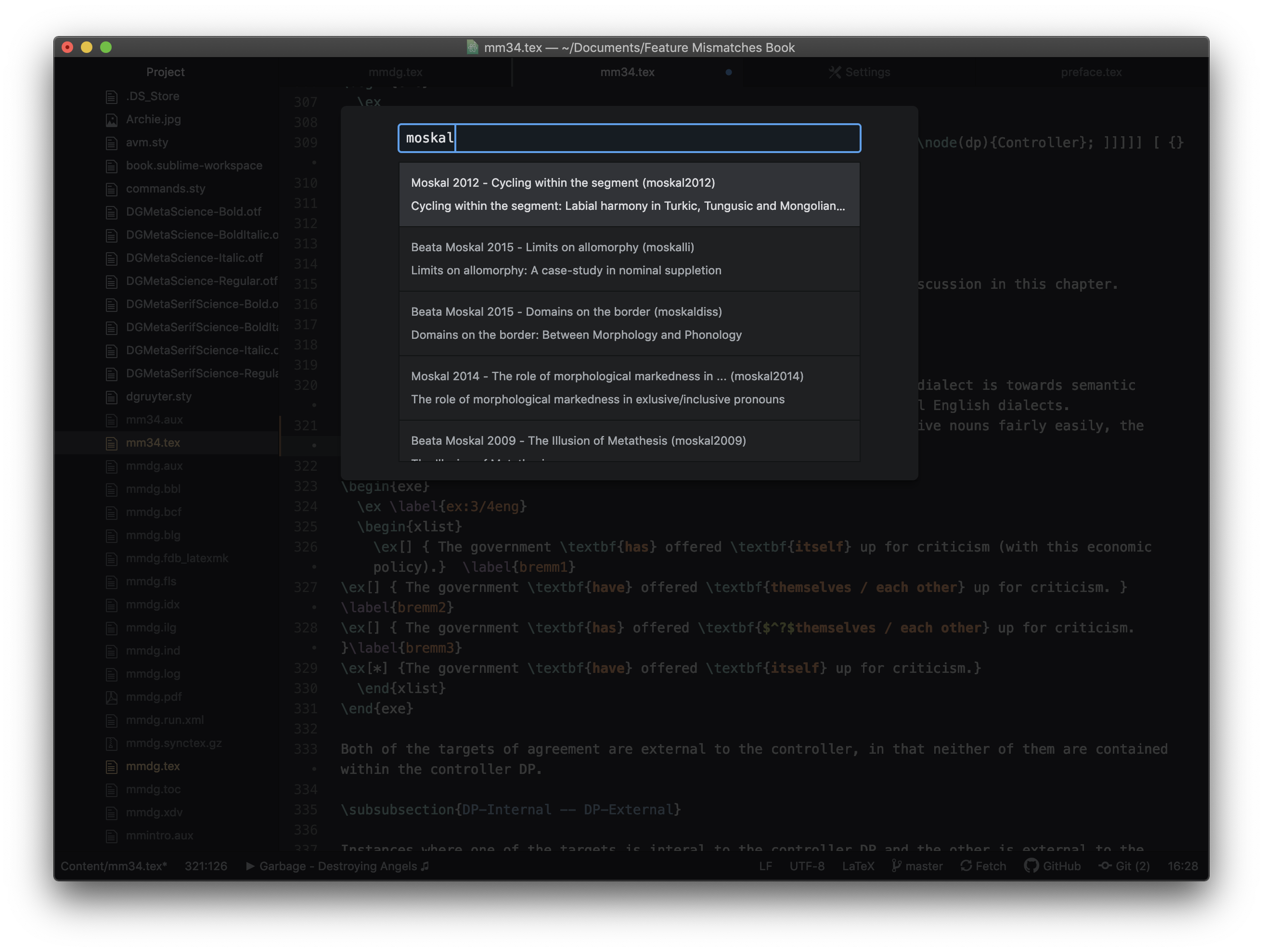

I can’t stress this enough. For many people, the entry into using LaTeX is the software that comes bundled with the download. I can’t speak for windows users here, but if you are a Mac user it’s not unlikely that your first foray into LaTeX use was using TeXShop. This is a very good program, is free to use and comes bundled with MacTeX (likely what you downloaded LaTeX with on your mac), and will get the job done. However, other editors offer a lot more customisation and shortcuts that are missing in TeXShop. For instance, Emacs, Atom (https://atom.io/) and Sublime all offer extensible options to make your writing easier. There’s also Microsoft’s Visual Studio Code, which is also fantastic, though I find slightly less suited to LaTeX than Atom or Sublime. All offer bibliography integration directly so you can search for citations in your bibliography file without leaving the program, useful if you know the name of the author of the source, but can’t remember the full citation key:

They also offer a range of syntax highlighting options and automatic indentation to make your text easier to read in the source file

Finally, they offer the ability to define your own keybindings and snippets.

Snippets for instance allow you to automatically insert a block of text by specifying a keyword.

For instance, one of mine is such that typing exe and hitting tab, causes the following code to appear, with the cursor placed after \ex :

\begin{exe}

\ex

\end{exe}

It’s a relatively simple one, but saves a lot of typing, and they can go as complex as you want.

Another of mine, tree + tab gives:

\begin{exe}

\ex

\begin{tikzpicture}[baseline]

\Tree [ ]

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{exe}

If you’ve ever written bulletpointed slides in beamer, having a shortcut to input:

\begin{itemize}

\item

\end{itemize}

will save your wrists, and add years to your life, I swear.

Type in Unicode

This is more of a preference than a necessity, but it comes with more benefits than you’d think. Typing phonetic symbols in LaTeX is traditionally the domain of TIPA. There’s nothing inherently wrong with TIPA: it’s a good package that allows for the output of the IPA. What more do you need? The problem with TIPA is what it does to your source code.1 Writing something simple in TIPA like the pronunctiation of placate /pləˈkeɪt/ will need the following code:

\textipa{pl@'ke1t}

And like I said, there’s nothing inherently wrong with this.

The problem is if you have a bunch of examples like this that you want to use elsewhere.

Suppose that you want to put them in an email, import them into a word document, put them in webpage or work with someone like me who doesn’t use TIPA.

You then need to manually go through the entire set of examples, manually chaning @ to ə, N to ŋ and so on.

A better way of working, which avoids all these problems is simply to input the code directly using unicode.

This can be tricky in the beginning but qiuckly becomes easier.

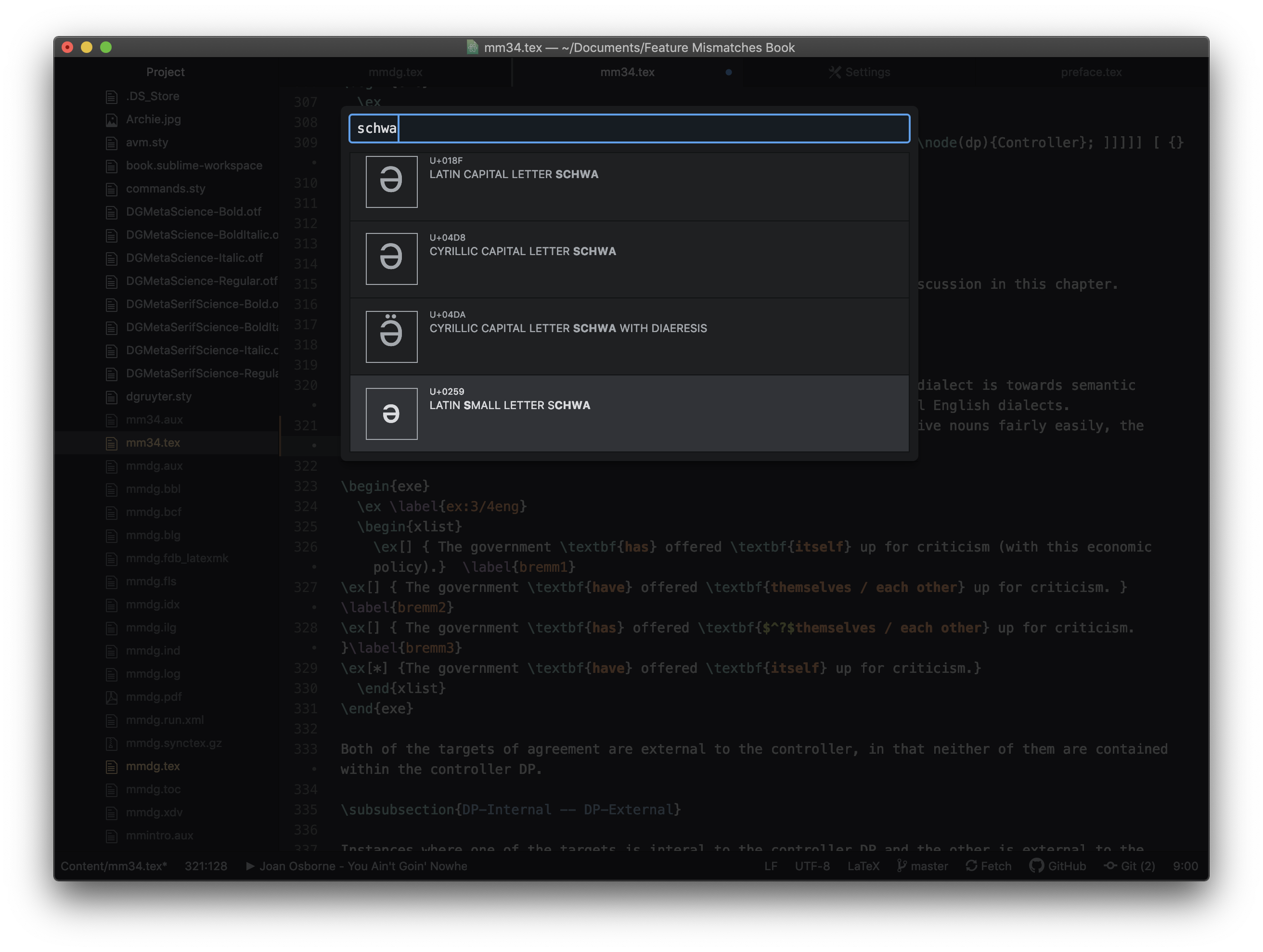

To do this, you need a good text editor, which allows you to enter unicode characters.2

Emacs does this natively with the sequnce ctrl+x 8 RET.

With both Atom and Sublime, you can download the excellent package Character Table (Atom) (Sublime), which allows you to search by either unicode combination or by character name:

Using unicode symbols also requires you to use XeLaTeX (or at least, not pdflatex) so that the characters can be recognised. You also need to use a font that outputs the characters, like Libertine, or the SIL fonts like Doulos or Charis.3

Using this method, in order to output /pləˈkeɪt/, you simply input /pləˈkeɪt/ into your document. And you can then copy-paste it into other formats: word documents, html documents, markdown and emails will all recognise the symbols, assuming that the font you’re using does too. Thus, in order to allow your data to be as easily used by other formats, you should be typing in LaTeX. If you never venture outside of LaTeX, then not using TIPA is not a big deal. But in my experience, it’s a matter of time before you want to use the examples outside of LaTeX, so it’s worthwhile getting familiar with unicode now. For a very worthwhile introduction specifically aimed at lingusits, I’d advise the (open access) book The Unicode cookbook for linguists BY Steven Moran and Michael Cysouw.

Use a local preamble

Yes, I know, use the preamble that’s appropriate for your paper, i.e. load only the packages that you need. However, at some point your LaTeX preamble (for the uninitiated, the set of packages you specify for LaTeX to use to do things not covered by the default compiler) will be a set of packages that you always use. Rather than having one document from where you copy-paste your preamble time after time, just store it locally. For instance, suppose that your preamble you use for everything is as follows:

\usepackage{fontspec}

\setmainfont{Linux Libertine O}

\usepackage[

backend=biber,

style=authoryear,

natbib,

url=false,

doi=true,

eprint=false,

maxbibnames=99,

useprefix=true

]{biblatex}

\addbibresource{<PATH TO YOUR BIBLIOGRAPHY>}

%%% Formatting and font

\usepackage{csquotes}

\usepackage{enumerate}

\usepackage{fontspec} % Font selection for XeLaTeX; see fontspec.pdf for documentation

\defaultfontfeatures{Mapping=tex-text} % to support TeX conventions like ``---''

\usepackage{xunicode} % Unicode support for LaTeX character names (accents, European chars, etc)

\setmainfont{Linux Libertine O}

%%% TIKZ

\usepackage{tikz}

\usepackage{tikz-qtree-compat}

%%% Other

\usepackage[normalem]{ulem}

\usepackage{pifont}

\usepackage{multirow}

\usepackage{amsmath}

\usepackage{amssymb}

\usepackage{xcolor}

\definecolor{bgblue}{HTML}{AECDF0}

\definecolor{bgblue}{HTML}{AECDF0}

\definecolor{hlblue}{HTML}{0C6FAB}

\definecolor{bgbluet}{HTML}{455260}

\definecolor{ngrey}{HTML}{949292}

\definecolor{linkgr}{HTML}{0b5496}

\usepackage{graphicx} % support the \includegraphics command and options

\usepackage{gb4e}

This is roughly what I use each time I write a document, or at least often enough that I like to have them always there.

Instead of continually either copy-pasting this from an existing file, or, god forbid, manually typing it time after time, it’s better to save the text in a file like packages.sty, and put it in a position that TeX will look (your PATH).

For Linux, this means in a directory USER > texmf > tex > latex > local (USER = your user account on the computer, you can normally just use ~ as a shorthand in place of USER, but not always).4

Then any files you store there will be visible to tex.

So, if you were to copy your usual preamble into the file packages.sty, and save it in the local directory (as just specified), then all you need is:

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{packages}

...

\begin{document}

**write paper here**

\end{document}

and TeX will use everything you specified in that file as part of your preamble to the document you’re writing.

Just fill in anything extra you need in your preamble where ... is in the above, and all your preamble is there.

Miscellaneous tips

- Don’t type a whole paragraph in a line in the text editor. When you use synctex to sync between pdf and your editor, synctex matches the part in the pdf with the line of code in the source file. So, if that line consists of a whole paragraph, you’ve narrowed the search down to, well a paragraph. Sure, you’re in the right part of the source code, but you still need to look through that paragraph manually to find the right place. A better practice is to make each sentence its own line in the source file. Thus, when you sync to a particular place, you get taken to that sentence in the source file, and so finding the precise place is a lot quicker. When writing, note that hitting

enterin the source file doesn’t start a new line in the output. Two sentences split over two consecutive lines is treated as part of the same paragraph. So there is no difference between:Here is the first sentence. And here is the second.And this:

Here is the first line. And here is the second.

Version Control: Learn Git

I’m not an expert on git by any stretch. I use it a lot for writing papers and for storing class grades, but use it less than a software developer would, which is to be expected, but here is a brief explainer why you should use it for your writing.

In short, git allows you to save different versions (snapshots) of a document within the same document.

That way, if you ever want to revert that document to a previous state you can.

To put it in terms of an example, let’s imagine you write a paper and have finished it, and send it to people for comments.

You get a comment back saying you should change section 2, and you do.

Then, you reread it, but don’t like what you changed, so you want to go back to the way it was.

How?

Yes, you can hit command + z to undo every change, but at some point, we need to recognise that this isn’t the best strategy.

Alternatively, you can do what a lot of people I know (and myself, in a previous life) and make a new version of the paper, so you keep the old version unchanged.

If you don’t like it, just use the old one again.

Again, it works, but it’s not a long term solution for good file storage.

With git, you can simply choose to save the document at a specific stage which will create a ‘commit’.

If you change it, you can choose which ‘commit’ to revert to.

Thus you only need one document on your system, and the entire history of that document will lie in that, along with meta-comments and a record of changes.

In short, it helps you avoid this.

It’s incredibly useful to have this record of past versions, to allow you to go back to other states, and feel free to alter text without fear of having to potentially re-type what you already did.

Another benefit is with collaboration. The biggest project collaboration I did was with Beata Moskal, Jonathan Bobaljik, Jungmin Kang and Ting Xu, which eventually appeared in NLLT. We did it the wrong way for a long time. Not in terms of content, but the way we worked on the same document was to share a document with Dropbox, and each would have access. Dropbox is a great service, but it’s not suited to this. It doesn’t allow for two people to work on the same document at the same time, meaning if person A works on the file while person B works on the file, one of you (or both, maybe?) will hit save, and a ‘conflicted copy’ will be created with that persons changes, while the other will save to the actual document, and their changes will appear in that. Eventually, we had to ensure that we let each other know when we were working on the file, so that no one else would try to at the same time. It worked, but about as well as you’d expect.

When I got sick of this, I set up the project on Overleaf, which is an online LaTeX editor that (at the time) allowed for multiple people to work on a LaTeX file at the same time online.5 So, whilst you don’t need to know git in order to get past the dropbox issue, I have my misgivings about Overleaf. Firstly, when I used it, the editor was terrible. It did what it needed to, but lacked the benefits I outline above about other text editors. It can also be frustratingly slow, the error resolving is not good, and now you need to subscribe in order to collaborate (€168, which is insane).

Git however, is smart enough to figure this out, and allow real-time collaboration. So, person A can work on the document, and commit their changes, while person B does so concurrently, and git figures out where each of the changes should lie in the document. Best of all, you don’t need to be online (like in Overleaf), but rather, you can pull the up-to-date version of the document and work offline, before pushing your changes when you connect again (great for working on trains and in cafes that lack stable wifi: hi Germany!).

There are some downsides. Introduction tutorials can be daunting,6 but it is possible to find some to explainers, e.g. here and collected here. I used to use the one by J. Alexander Branham, but his website has disappeared, sadly.

Two further things to mention. Git allows you to sync things across computers. Git works best when you pair it with a remote repository, hosted by, for instance, github or gitlab. Both of these offer free services for non-commerical use, private repositories and are very stable. If you push your document to one of these, you can clone it on a different computer, work on the changes there, and before pushing the changes, and accessing them at your own computer. This allows for easy syncing between home and office, for instance. Think of it like dropbox, but for text files.

Secondly, it will only work right with plain text files. That means, you get all the benefits that git offers for .tex, .txt, .py, .js, .html, .css etc., but non-text files like .docx, .pdf, or .png — whilst able to be tracked and shared — won’t show version history. So, if you are going to use git, you need write in plain text (realisitically either LaTeX or markdown for most linguists), and if you are going to write in plain text you should be using git.

Don’t be afraid to look beyond LaTeX and LaTeX defaults

Whilst I maintain that LaTeX is the best way to write articles, that doesn’t mean that it’s the only thing out there, for all purposes. I’ve concentrated on article writing above, but a lot of people use LaTeX for a variety of other reasons, notably making slides with beamer. There’s nothing wrong with beamer: I’ve used it a lot and am very happy with the results.

However, let’s face it, the default beamer formats are quite uninspiring. There’s not a whole lot of them, lots of people use them, so many beamer slides look the same. Yes, this is a question of aesthetics, which shouldn’t be foremost in your mind when preparing slides, obviously the content is far more important. But, a slide show that is well set out in terms of content and looks good can make a big difference to how the audience responds to your talk. So, here are a couple of tips.

Use other beamer themes

Look around online and you’ll find a lot of these, where people have created to get away from the beamer defaults. The best that I’ve seen, is Metropolis, which looks great. Otherwise, with a little bit of time, you can create your own. Building on this StackExchange answer, I built my own, which I’m pretty happy with.

Stay away from the junk at the top of slides

I’ve seen a lot of presentations with beamer, and it’s depressingly often that the top quarter of the screen is taken up by a constant table of contents, with progression guides. I’ve never understood the point here (though fallen into the trap myself in the past). What is this supposed to achieve? I can see in principle a benefit: that the speaker wants to allow the audience to follow the strcture of the talk. However, it’s emminently possible to do this in the beginning of the talk, and before transitions between sections. In practice, having a constant guide at the top only allows me to check when the talk is going to end, or which bits I can tune out of before something relevant will happen. So, I may be alone here, but get rid of the guide: it’s unnecessary, takes up space that could be better used for content, and often distracts from your talk.

For the love of everything, don’t copy-paste an article or a handout into slides

I’ve also seen this a lot. Beamer is LaTeX, so therefore, LaTeX code makes up the slides. Therefore, you can just copy-paste parts of a paper into slides. Right.

I’ve seen people copy-paste paragraphs and multiple sentences into a slide bullet point. Often this is because they make a handout to go along with the talk, and the slides are formed from the handout. But, don’t. Just, don’t. Making captivating, easy to follow slides is a lot different from making a handout. Slides should be used as a support to the narrative, detailed handouts are used also as support but also to allow people to follow at home without the talk. They are not the same thing and require different layouts.

Look at alternatives

Whilst the major benefit of beamer is that it slots easily into your LaTeX workflow, there are other options. It’s possible to write slides in markdown, and convert them to a variety of formats using pandoc. One of my favourites here is the html based options, especially reveal.js. This is a javascript based, and will produce slides in html format that you can style using css. No, it’s not perfect, and you have to fiddle with it to get it right for a lingusitics talk (I’ll blog more about this soon), but the results are impressive.

Notes

-

Aside from the difficulty it causes using XeLaTeX. ↩

-

Actually, that’s not really necessary. If you are using OSX, you can insert characters using the option ‘insert Emoji and Symbols’. Presumably something similar exists on windows. Alternatively, you can write unicode directly using keyboard combinations, at least on Linux. ↩

-

This is not an exhaustive list of unicode capable fonts, just the ones that I’m familiar with. ↩

-

It’s needlessly slightly more complicated on OSX. You need the file directory

USER > Library > texmf > tex > latex > local, and for reasons I don’t understand, Apple treats each user’s Library file as a hidden one. You can get there from the finder by followingGo > Homein the menu (or hitcommand + shift + b), which will take you to the user directory. Then, typecommand + shift + .to show hidden files. Make the directorytexmf > tex > latex > localthere, and anything you put there should be visible to LaTeX. ↩ -

Overleaf is actually based on git, or was, I believe. ↩

-

Github for instance, while a wonderful service, really needs a tutorial that doesn’t try to pack everything into one go. ↩